"It is very likely that nearly every one has been very nearly certain that something that is interesting is interesting them" — Gertrude Stein

29 June — Tuesday

§ Caetano Veloso | A Foreign Sound | Nonesuch 79823-2 | 2004

A month or two into owning this disk, I tend to skip "Feelings" and "It's Alright, Ma (I'm Only Bleeding)," but I like just about everything else, especially the versions of Eden Ahbez's "Nature Boy," Kurt Cobain's "Come as You Are," Irving Berlin's "Blue Skies," Arto Lindsay (et al)'s "Detached," Rodgers and Hart's "Manhattan," Cole Porter's "Love for Sale," and Irving Burgie's "Jamaica Farewell." The purest instance of Veloso's estrangement of anglophone song? The moment in David Byrne's "(Nothing but) Flowers" where, thrown by the voicing of "w" and retreating to a deceptive eye-rhyme, he sings: "if this is paradise / I wish I had a loan mau-wer."

7 June — 21 June

§ 24: Season One | 20th Century Fox | 6 DVDs | BBC Episode Guide (contains spoilers) | Fox site (ditto)

16 June — Bloomsday

§ Poetry blogs — noonish

"Der Bingle nails" Babel "to the wall" at the soon-to-be hooded (in the PhD, not the Abu Ghraib, sense of the word) Konvolut M. • Billboard interpellation at The Well-Nourished Moon. • Cahiers de Corey kicks in a conversion narrative. • Silliman reviews Anne Waldman's In the Room of Never Grieve. Of her work at Naropa, he writes: "Anne Waldman makes James Brown seem slothful & Charles Bernstein positively indolent. She’s not only paid her dues, but yours, mine & that of more than a few other people as well." • A chance encounter between Equanimity and Fait Accompli at St. Mark's Book Shop leads to chat of slumping blog stats, Smithson, and L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E, all capped by a Stephen Wright sighting. • Hotel Point channels Friedlander channeling Poe. • Piranesi, Goncharova, Akhmatova, Bloomsday, Canadian politics, and more at the prolific wood s lot. • Snippets from an interview with Jessica Grim at Vanishing Points of Resemblance. • And lipstick-tracing Mikarrhea's moved: update links accordingly.

15 June — Tuesday

§ Poetry blogs — noonish

Silliman on Jarmusch's Coffee and Cigarettes: "The film is immanent in the way that much of Robert Creeley’s poetry is – pay attention to what is in front of you here." • Equanimity cracks open a carton full of new Burning Deck books. • Cahiers de Corey comes to the "crazy high speed chase through thousands of years of Chinese history" that are Cantos 52-61. • Fait Accompli channels Hazlitt circa 1839 on the loss of authorial aura:"The poet, as of old, is not now, from rarity, regarded as a mystery, a wizard, a something whose privacy is not to be profaned by being encroached upon; every effort is made to throw down this partition wall, to rend asunder the veil of genius; and instead of being kept at a studious and awful distance, he must be brought near, must be shown as a *lion*, must be had out to dinner, or to an AT HOME; we must procure his autograph, get him to write his name in an *album*, and, if possible, come into personal contact with him, so as to mix him up with our daily impressions and admiring egotism." • And special thanks to Mikarrhea for the kind words about this site.

14 June — Monday

§ Poetry blogs — noonish

Lime Tree files an Orono report. • "The Governor catches bullets in his mechanical teeth" at Cahiers de Corey. • The indulger is undone at Mikarrhea. • Provoked, Sugarhigh! calls for more "rage that seroconverts to joy in the bloodstream." • Overlap reads Michael Magee's MS: "Goofy thematic fugue-like development. Ronald Johnson in science of perception mode if he had gone through the poetics of Jackass.... Riff-based paratactic sequencing with active morphing." • And Pantaloons dips into Anne Tardos's The Dik-dik's Solitude: "Clack mopery. Documenta flop-flop." • "Of course, doing nothing means thinking, a kind of catatonia": Magee, Friedlander, Poe, Clouseau, Caledonia, and Rich Little at Hotel Point. • Silliman leads with thoughts on Jack Hirschman, Third Worldism, and "what it would take to put together a genuinely global coalition of wage slaves, the only sort of labor movement that could ever avoid being sliced & diced at will by the divide-&-conquer machinations of capital," then segues into "how great Lorenzo Thomas is." "As to my 'thoughts on revolutionary poetry," he concludes, "when it’s well written, I like it just fine." • Konvolut M on gigs by Mission of Burma and Refrigerator; also, film notes on The Stepford Wives ("I was hoping for a more saturated, hyper-something visual style, esp. from Frank Oz, but this was pretty tame") and The Five Obstructions ("I was hoping for a cinematic Eunoia, and it's considerably less than that").

10 June — Thursday

§ Poetry blogs — early afternoon

Konvolut M learns five things on a visit to Santa Monica Pier. • While Sugarhigh! decides between five white girls. • Far along the Guermantes Way, Silliman finds himself immersed in Proustian temporality. • The Cahiers de Corey test the "dangers and pleasures of Circe's island" while working through Cantos 31-41: "I have eaten the flame" (Canto 39). • Equanimity savors the "admirable combination of severity and affection" to be found in Benjamin Friedlander's Simulcast. • And Nemski prints out a summer's worth of reading that includes Coolidge, Armantrout, Williams, and Olson.

9 June — Wednesday

§ Times Literary Supplement 5278 | 28 May 2004

Peter Brooks reviews François Cusset's French Theory: Foucault, Derrida, Deleuze & cie et les mutations de la vie intellectuelle aux États-Unis: the book "is full of insights and far-reaching interpretations. It is written both with a kind of French intellectual snobbism (possibly an ineradicable part of one's birthright as a French intellectual) and much sympathy for the bizarre forms of American cultural life. Although he probably exaggerates the impact of French theory in America, he seems to me largely right in his understanding of the kinds of differences it has made. He makes many a mistake of detail, in dates and names and such, but this doesn't alter the value of the whole. Above all, he write from a deep and distressed appreciation of how thoroughly French intellectual life has abandoned the generous and exciting reach of the 1960s and 70s—how it has fallen back into the anti-'May '68' patterns prescribed by such as Jean-Luc Ferry and Bernard-Henri Lévy, into a 'new humanism' which is often moralistic rather than thoughtful" (5). • Darryl Pinckney reviews William J. Maxwell's edition of Claude McKay's Complete Poems: "Maxwell has edited this comprehensive volume superbly, hunting down every last poem [there are 323 all told], and although Complete Poems may not enhance McKay's reputation as a poet, the work is certainly an addition to his biography in that the poems...record the changes in his thinking and ideological allegiances over the years" (10). • Jules Smith reviews the Zukofksy - Williams correspondence edited by Barry Ahearn and Zukofsky's study of Guillaume Apollinaire edited by Serge Gavronsky as part of the Wesleyan Centennial Edition of Zukofsky's complete critical writings. Smith argues that "both books suggest some modification to Zukofsky's image as reticent and austere. In this, the centenary year of his birth, he emerges in both letters and criticism as a more humorous, even flamboyant figure, but also more single-minded in the pursuit of career-success. At least within the tight circle of his friends and family, Zukofksy was witty, highly sociable and in his publishing projects highly collaborative" (11). • Marjorie Perloff reviews the Duncan-Levertov correspondence, finding theirs to be a "world of poetry as vocation—poetry as vision, special knowledge and epiphany" (all suspect terms for the critic). Mistakenly naming Mitch Goodman as one of the Chicago Seven, Perloff views with suspicion the anti-Vietnam War convictions of the poets, asking "why these once apolitical poets—whose correspondence has virtually nothing to say about the Cold War and the revelations of genocide coming from the Soviet Union—suddenly become activated in response to Vietnam" (13). Noting the famous break between Duncan and Levertov on precisely the issue of poetry's responsibilities in a time of war, Perloff argues that "they could only blame each other for what were, in the end, their own shortcomings" (13).

7 June— Monday

§ Poetry blogs — midday

"'Reagan's dead!' I called out cheerfully" (Bloggedy Blog Blog). • Unpleasant Event echoes "Let Them Eat Jellybeans." • Silliman declares "Lubaschism is post-avant in tone, neo-classical in spirit." • Pantaloons marvels at "how un-antique John Cage's music sounds." • Which reminds me of the film Lipstick, where the failed experimental musician, and soon-to-be rapist, tells Margaux Hemingway of being snubbed by "Sean Gage." • Gerritt Lansing, Michael Magee, Ange Mlinko, and Carol Snow are shown to their rooms at Hotel Point. • Cahiers de Corey tells of two new Barrow Street publications. • Festival photos from Carrboro at Never Mind the Beasts. • To which Nice Guy Syndrome supplies some captions. • Fait Accompli crushes blogs. • Mosses from an Old Manse welcomes the DVD of Visconti's The Leopard. • And I'm glad to learn from p-ramblings that Deborah Meadows, whose Tinfish chapbook I much admired, now has a full-lenth volume from Green Integer.

§ Bookforum 11.2 | Summer 2004 | 56pp | $3.95 | online edition not yet updated

First pass: John Palattella reviews Kenneth Fearing's Selected Poems, now out from the Library of America: "the stagnation and devastation at the core of Fearing's best hard-boiled rhapsodies, where many people experience the barrenness of failure while a few enjoy the emptiness of success" (46). • Brian Lennon responds very intelligently to Sven Birkerts's lament for criticism in the last issue. "My point," writes Lennon, is "that there is no time for reading in most nonacademic American lives. I don't mean being able to get through a book in a week; I mean being able to get through a book in a day, or parts of three or four or five books in a day, if you need to. More important, I mean acquiring a feel for current debates in philosophy, political theory (across the spectrum), economics, and the physical and other social science, as well as the arts and art criticism—and in at least one or two other major national or regional contexts...in addition to one's own" (31). Later, recalling the four years during which he regularly wrote reviews: "Did anyone really read the review then? Did even my own editor read it? Did the marketing reps who blurbed the reviews (and misspelled my name underneath) read them? Did only rival book reviewers (whoever they might have been) read them? In the end, book reviewing didn't seem part of anything I could really call 'work,' in either sense of the private and cumulative or the public and collaborative. Book reviewing was another monologue in the the literary life, no different from writing the books themselves, but with far less prestige. It was time that I withdrew from my life, without any chance of ever getting it back—the way that you do get it back, in a way, when someone talks back to you, even a little" (33). • Max Winter admires Jeff Clark's Music and Suicide, calling it more "worldly" and "courageous" than The Little Door Slides Back: "The 'I' in these poems is less a pronoun than a vehicle for an unmitigated nakedness that his debut did not possess; the new poems act as simple, near-lyrical statements without apology" (52). • Andrew Ross writes of China's transition from the world's factory to the world's outsourced office: "Its Labor Ministry recently launched a drive to train an additional one million workers in occupations it labels 'gray-collar.' This is a broad category, covering everything from fashion designers to software engineers, from ad writers to numerical-control technicians. Some of these occupations are the sweet ones favored by every large city looking to promote its 'creative sector'—after all, the presence of artists and arts industries boosts real-estate prices and attracts fancy investments. The less glamorous ones are even more essential if China, courtesy of its foreign investors, is going to be able to sustain its long march up the value chain. While not exactly on the scale of building the Three Gorges Dam, this sizable HR effort is a sobering addition to the list of favors that governments usually offer to the beneficiaries of so-called free trade: virtually free land, oodles of tax exemptions, and a soft guarantee that labor laws (on paper, some of the best in the world) will never be enforced" (36). • And Sarah Kerr adds to the stack of reviews I've lately seen of Craig Seligman's Sontag & Kael: Opposites Attract Me. According to Kerr, Kael's "groundbreaking celebration of beautiful throwaway moments in otherwise negligible works has been assimilated to the point of cliché" and "the milieu that lent urgency to Sontag's earliest writing" is gone. Citing Seligman's remark that Kael's "sentences get their nervous agitation not from self-doubt, of which she had none, but from impatience, the arguer's impatience with those who don't get it," Kerr closes by counseling "aspiring young critics" to "spend a little less energy on impatience with those who fail to get it" (20).

31 May — Monday

§ Johnny Guitar | Dir. Nicholas Ray, 1954 | DVD, 110 min | IMDb link

29 May — Saturday

§ The Day After Tomorrow | Dir. Roland Emmerich, 2004 | Theatrical release, 124 min| IMDb link

28 May — Friday

§ The Hole: 2000 seen by... | Orig. title Dong | Dir. by Tsai Ming-liang | DVD 95 min | IMDb link

"The Hole is even more contemplative than Vive l'Amour, the only one of Tsai's films to have a local release. Dialogue is minimal (as is contact between the characters). There are no exteriors; most compositions are in middle shot and the camera is generally fixed. The takes are long and underscored by the near-constant sound of cascading water. Still, The Hole has an absurdist, gross-out undercurrent. The plague, which a French scientist names Taiwan fever, is carried by cockroaches and infects humans with roachlike behavior — scuttling around on all fours, hiding from the light. As this soggy armageddon suggests the peripheral scenes from a cheap horror flick, The Hole's deadpan object comedy—featuring an umbrella and a green plastic basin among other things—has intimations of Jacques Tati" (J. Hoberman writing in the Village Voice in March of 1999).

25 May - 27 May

§ Sex and the City | Season 6, Part 1 (episodes 1-12) | DVD | IMDb link

Coming off the sluggish fifth demi-season, these punchily-constructed episodes are a colorful, funny, flauntingly brand-driven, escapist return to form.

25 May — Tuesday

§ Roger D. Hodge | "Weekly Review" | Harper's on-line | link

"Bad people have celebrations, too."

24 May — Monday

§ Troy | Dir. by Wolfgang Petersen, 2004 | Theatrical release 163min | IMDb link

James Horner's ludicrous score, the tie-dye and halter-top moments in Bob Ringwood's costuming, the decision to deliver already-stilted lines with British (and Australian) accents, and Brad Pitt's largely uncomprehending performance are all still not amusing enough to push Troy solidly into the "so bad it's good" category—it is in fact just plainly and slowly terrible. But not everything about the film is equally lame: it's interesting to see the thousand ships, for instance, and Eric Bana as Hector, the wraith-faced Peter O'Toole as Priam, and Orlando Bloom as a prettier-than-Helen Paris all acquit themselves well enough. Sean Bean's take on Odysseus is pretty much invalidated by the worst "aha—I've got it" moment I've seen lately (maybe in my life), but he does seem in the vicinity of a good performance now and again. And Brian Cox's Agamemnon is played with gusto, if not nuance. The real problem is the script, which begins by destroying the temporal frame of the tale and ends in absurdity with the slaying of Agamemnon by an erstwhile virgin priestess of Apollo whose love for her captor Achilles the film doesn't even attempt to explain (apparently Pitt the irresistible is extra-diegetic reason enough). The one consolation is that some future incarnation of Mystery Science Theater 3000 will have plenty to work with!

23 May — Saturday

§ Susan Sontag | "Regarding the Torture of Others" | New York Times Magazine | 23 May 2004 | link to on-line version (registration required) | link to Guardian version (slightly different; no registration required)

"Shock and awe were what our military promised the Iraqis who resisted their American liberators. And shock and the awful are what these photographs announce to the world that the Americans have delivered: a pattern of criminal behavior in open defiance and contempt of international humanitarian conventions. Soldiers now pose, thumbs up, before the atrocities they commit, and send off the pictures to their buddies and family. Should we be entirely surprised? Ours is a society in which secrets of private life that, formerly, you would have given nearly anything to conceal you now clamor to be invited on a television show to reveal. What is illustrated by these photographs is as much the culture of shamelessness as the reigning admiration for unapologetic brutality. The notion that 'apologies' or professions of 'disgust' and 'abhorrence' by the president and the secretary of defense are a sufficient response to the systematic torture of prisoners revealed at Abu Ghraib is an insult to one's historical and moral sense. The torture of prisoners is not an aberration. It is a direct consequence of the with-us-or-against-us ideology of world struggle with which the Bush administration has sought to change, charge radically, the international stance of the United States and to recast many domestic institutions and prerogatives. The Bush administration has committed the country to a pseudo-religious doctrine of war, endless war—for 'the war on terror' is nothing less than that. What has happened in the new, international carceral empire run by the United States military goes beyond even the notorious procedures in France's Devil's Island and Soviet Russia's Gulag system, which in the case of the French penal island had, first, both trials and sentences, and in the case of the Russian prison empire a charge of some kind and a sentence for a specific number of years. Endless war is taken to justify endless incarcerations—without charges, without the release of prisoners' names or any access to family members and lawyers, without trials, without sentences. Those held in the extra-legal American penal empire are 'detainees'; 'prisoners,' a newly obsolete word, might suggest that they have the rights accorded by international law and the laws of all civilized countries. This "Global War on Terror" (GWOT)—into which both the justifiable invasion of Afghanistan and the unwinnable folly in Iraq have been folded by Pentagon decree—inevitably leads to the dehumanizing of anyone declared by the Bush administration to be a possible terrorist: a definition that is not up for debate and is usually made in secret" (Guardian version).

22 May — Saturday

§ The Fog of War: Eleven Lessons from the Life of Robert S. McNamara | Dir. Errol Morris, 2003 | 107min DVD | IMDb link | Below, photograph of Tokyo street after 1945 firebombing that killed 100,000 people. An "efficiency report" authored by McNamara led to the strategy.

§ Scott Sherman | "The Rebirth of the NYRB" | The Nation | 7 June 2004 | 16-21 | online version

Sherman argues that the editors of the New York Review of Books—Robert Silvers and Barbara Epstein, both of whom have been at the journal since its founding by Elizabeth Hardwick, Robert Lowell, and Jason Epstein in 1963—have "met the challenges of the post-9/11 era in a way that most other leading American publications did not..." (21). • "What blew the dust off The New York Review? In no sense, really, has the paper returned to its New Left sensibility of the late 1960s: Chomsky, Hayden, and Willis have not been reinstated; young lions like The Baffler's Tom Frank and The Village Voice's Rick Perlstein have not been invited to contribute; Eric Foner, Bruce Cumings, Richard Rorty, Chalmers Johnson, Stephen Holmes, Anatol Lieven, Elaine Showalter and Carol Brightman continue to publish much of their finest work not in The New York Review of Books but in the more radical, eccentric and sprightly pages of the London Review of Books. In short, the Review's liberal (and establishment) soul remains intact. What has changed significantly, in the age of Bush, is the Review's style of rhetoric and degree of political focus and commitment" (17).

20 May — Thursday

§ Les Demoiselles Ont Eu 25 Ans | Dir. Agnes Varda, 1993 | 63min | IMDb link

Varda returns to Rochefort twenty-five years after the town was occupied and transformed by Jacques Demy's movie crew. A charming first draft of a portrait she'll complete with her 1995 L'univers de Jacques Demy.

19 May — Wednesday

§ Rear Window | Dir. Alfred Hitchcock, 1954 | VHS, MCA 1984 | 112min | IMDb link

I'm past the point of seeing new things in it, but familiarity does nothing to diminish this taut, wry, and subtly malicious masterpiece.

Late April, Early May — Scattered Impressions

Screen Memories: Victim (dir. Basil Dearden, 1961); Thelma & Louise (dir. Ridley Scott, 1991); Les Triplettes de Belleville (dir. Sylvain Chomet, 2003); The Graduate (dir. Mike Nichols, 1961); Life of Brian (dir. Terry Jones, 1979); Le Voyage à Reykjavik (dir. Alexandre Delay & Emmanuel Hocquard, 1997); Lipstick (dir. Lamont Johnson, 1976) and Cléo de 5 à 7 (dir. Agnes Varda, 1961). • In the air: a fair amount of opera, plus Caetano Veloso's A Foreign Sound. At a first listen the latter reminds me too much of the soporific late-career Fred Astaire record, Steppin' Out (Verve 1952), but the phrasing in the live version of "Nature Boy" (performed on Charlie Rose on May 11th) got to me & I expect several other tracks will as well. • Staring at, like everyone else: the digital images depicting U.S. treatment of Iraqi prisoners held at Abu Ghraib. Luc Sante's op-ed in the Times got nearer to what we're looking at than most commentators were able to, and the Well-Nourished Moon got at the contradictions of "living in this leafy comfort as afforded by constant damage elsewhere." • Looking at, distractedly, in crowded rooms: the Whitney Biennial, where I liked work by Cecily Brown, Chloe Piene, Mary Kelly, Terence Koh—and perhaps most (and least) of all, Jim O'Rourke's sound installation in the men's room.

20 April — Tuesday

§ Roger D. Hodge | "Weekly Review" | Harper's | link

19 April — Monday

§ Sherman Alexie | "Without Reservations...an Urban Indian’s Comic, Poetic, and Highly Irreverent Look at the World" | Performance at the Maine Center for the Arts

The proof that Alexie had material to burn came during the Q&A that followed his carefully structured hour-long stand-up routine: only two questions could be asked, so ample and hilarious were his answers.

18 April — Sunday

§ Smoke Signals | Dir. Chris Eyre, 1998 | DVD 88min | IMDb link

16 April — Friday

§ Persona | Dir. Ingmar Bergman, 1966 | DVD 83min | IMDb link

15 April — Thursday

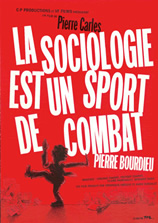

§ Sociology is a Martial Art (La Sociology est un sport de combat) | Dir. Pierre Carles, 2001 | VHS 146min | IMDb link

Director Pierre Carles presents an admirable portrait of Bourdieu in the last year or so of his life—vigorous, self-deprecating, gamely attempting, in one impossible situation after another, to explain his thinking about art, social determination, neo-liberalism, masculine domination, and a host of other phenomena. I approached the film nervously, unsure how it might affect the decade or more I've spent reading and valuing Bourdieu's work, but I walked away impressed both with the film and its subject.

9 April — Friday

§ Pola X | Dir. Leos Carax, 1999 | Dir. of Photography Eric Gautier | DVD 134min | IMDb link

Carax's adaptation of Melville's Pierre, or the Ambiguities. • "The movie itself is chaotic. Some characters aren't identified, and others abruptly disappear then unexpectedly return. The acting, although intense, only fitfully rises to the mythic level the director is aiming for. Mr. Carax is much better at creating pungent atmospheres than at structuring scenes. But Pola X still has its share of dazzling and disturbing images: besides the industrial landscape, a bride on a pedestal being fitted for a gown, lovers grappling in an ominous semi-darkness, a woman streaking through the night on a motorcycle that suddenly crashes" (Stephen Holden writing for the NYT, link requires registration).

6 April — Tuesday

§ Roger D. Hodge | "Weekly Review" | Harpers | link

4 April — Sunday

§ Gilberto Perez | "Self-Illuminated" | Rev. of Godard: A Portrait of the Artist at 70 by Colin MacCabe | London Review of Books | 1 April 2004 | 3-6 | link

"The look of available light, which Godard developed in his films with [Raoul] Coutard and has consistently pursued with other cinematographers, is central to his films' mixture of palpable actuality and manifest artifice. Whatever it is—it's obviously not just a matter of leaving the camera open to the light of things in the world—no one else does with available light what Godard does, which brings about a singular beauty. 'Everything beautiful,' Novalis said, is 'self-illuminated.' Godard's images have that quality" (5). • Whereas Jones (see below) likes best the films made with Anne-Marie Miéville in the 1970s, Perez likes just about everything except those: since "Nouvelle Vague, which he made in his sixtieth year, he has been having a moment of old age that can stand beside the works of his youth" (6).

§ Kent Jones | "Two or Three Things About Him" | Rev. of Godard: A Portrait of the Artist at 70 by Colin MacCabe | Bookforum | Spring 2004 | 24 | link

MacCabe's tome is overly devotional for Jone's taste, though it "does nail two aspects of Godard's output that will keep it forever fresh: the complete absence of the shot-countershot structure that has been a staple of narrative cinema since the '20s and his utterly unique approach to color, light, and space, rethought in their organizational and expressive properties on a project-by-project basis." • "In the end, it's not the individual films that have made Godard so influential, the jump-cutting in Breathless aside. In essence, I think it has to do with the way he has cultivated his identity as the grand demiurge of the moment when he came of age. In one way or another, his films all revolve around the high drama, poignance, and considerable charisma of postwar Paris, when the flood of American movies suppressed by the Germans and a moribund French film industry dovetailed with the crisis of representation brought on by the Holocaust to create a form of spontaneous combustion—from which emerged a pack of angry, talented, morally self-conscious young men ready to raise the roof off the French film world."

§ Adam Cohen | "The Intellectual Imperialists" | Rev. of Free Culture by Lawrence Lessig | New York Times Book Review | 4 April 2004 | 12 | link requires registration

"For the silliness to which copyright battles frequently descend, it is hard to improve on Lessig's story of the Marx brothers telling Warner Brothers, after it threatened to sue if they did a parody of 'Casablanca,' to watch out because the Marx brothers 'were brothers long before you were.'"

2 April — Friday

§ Heart of Glass | Dir. Werner Herzog, 1976 | DVD 94min | IMDb link

"[W]hether Herzog actually 'hypnotised' the cast, or merely directed them to give hypnosis-type performances — or even if he sedated them by chemical means — doesn't ultimately matter. Whatever the process, the results are often agonisingly protracted, with heavy-lidded rustics intoning their lines in a robotic monotone. The effect extends to the viewer, and we may find ourselves being sucked into this sleepy world of nightmarish stasis. It's the horror, ultimately, of failed progress — as the world teeters on the cusp of a brave new industrial era, the crisis in the glassworks (a spectacular instance of "trouble at t'mill" indeed) opens the possibility that the whole of humanity may actually be poised on the precipice of a terrible abyss" (Neil Young writing for Jigsaw Lounge).

28 March — Sunday

§ The Swimmer | Dir. Frank Perry, 1968 | Dir. of Photography David L. Quaid | DVD 95min | IMDb link

"Lancaster is terrifying as Merrill. His powerful body, combined with the mechanical, rote way in which he utters social pleasantries, only to return the conversation to his aquatic quest at first opportunity, unnerves the viewer as much as it does the friends who seem to be granting him pool-access the way one indulges a street-crazy — anything to end the encounter and return to normalcy. Lancaster is frightening in this film in a way he's never been in anything else. As his façade cracks, bit by bit over the course of two hours, there is a gradual realization of just how much is wrong here, and exactly what form that wrongness is taking; it comes like a series of hammer-blows to the gut. ¶ Equally awful, though, is the social scene Merrill crashes through, as he first sprints, then clambers, and finally trudges from one pool to the next. The braying laughter, the omnipresent alcohol, and the sheer glassy-eyed vapidity of the conversations all combine to paint a nightmarishly detailed portrait of a world that could quite easily drive a man insane and force him to seek solace underwater" (Phil Freeman writing for CultureVulture). • Read Konvolut M on Perry's 1972 adaptation of Joan Didion's Play It As It Lays.

27 March — Saturday

§ Le Divorce | Dir. James Ivory, 2003 | DVD 117min | IMDb link

"Only [Thierry] Lhermitte [as a telegenic right-wing lothario] and Glenn Close, as an aging literary expatriate, find the right notes of wry Jamesian comedy, and this is because they alone seem able to let their vain, self-aware characters unfurl a bit. The virtue of [Diane] Johnson's novel lay not in its profundity—a comedy of manners is by definition an affair of surfaces—but in its sparkle and its speed, qualities notably lacking in Mr. Ivory's direction" (A.O. Scott writing for the NYT). • I'm always surprised by the offhanded brutality with which comedies like this one treat their non-comedic elements, here an attempted suicide by a pregnant American poet who's been jilted by her French husband and, later, the murder of same straying husband to nobody's apparent remorse: a cut and a cute remark later, we're back to that "surface" of which Scott speaks above, with all that we know about such acts and their consequences left awkwardly outside the frame. • As the film heads into its predictable finish (better husband to replace dead one, etc.), we learn that Naomi Watts has had her book of poems accepted by "Loaf of Bread Press."

26 March — Friday

§ About Schmidt | Dir. Alexander Payne, 2002 | DVD 125min | IMDb link

"About Schmidt is essentially a portrait of a man without qualities, baffled by the emotions and needs of others. That Jack Nicholson makes this man so watchable is a tribute not only to his craft, but to his legend: Jack is so unlike Schmidt that his performance generates a certain awe. Another actor might have made the character too tragic or passive or empty, but Nicholson somehow finds within Schmidt a slowing developing hunger, a desire to start living now that the time is almost gone" (Roger Ebert writing for the Chicago Sun-Times).

24 March — Wednesday

§ Sven Birkerts | "Critical Condition: Reading, Writing, and Reviewing: An Old-Schooler Looks Back | Bookforum | Spring 2004 | link

"And this is more or less where we find ourselves now. Psychologically it is a landscape subtly demoralized by the slash-and-burn of bottom-line economics; the modernist/humanist assumption of art and social criticism marching forward, leading the way, has not recovered from the wholesale flight of academia into theory; the publishing world remains tyrannized in acquisition, marketing, and sales by the mentality of the blockbuster; the confident authority of print journalism has been challenged by the proliferation of online alternatives."

22 March — Monday

§ "Invisible Jukebox: Damon & Naomi" | The Wire | January 2004 | now online here

"DK: Is it Quicksilver?

[Wire]: Wow, you're batting a thousand today."

19 March — Friday

§ George Washington | Dir. David Gordon Green, 2000 | Dir. of Photography Tim Orr | 89min | DVD Criterion Collection | Screened in the Devil's Eye Film Series curated by Justin Andrews at the University of Maine | IMDB link

"Green's arty, scene-setting montage, his use of slight slow-motion underscored by a portentous drone-tone, the movie's skewed voice-over narration, its sumptuous Cinemascope compositions, and lush bucolic mood remind many people of Terrence Malick. This modest movie is draped in visual grandeur, like a kid trying on an overlarge suit—far from overweening, the effect is oddly disarming. (To add to the mystery, cinematographer Tim Orr gets an onscreen credit nearly equal to Green's, but barely a mention in the press notes.) [...] For all its troubling incidents, however, what's most shocking about GW is its tender regard. The movie is unabashedly utopian. (Green lived communally with the cast and crew during production.) It also suggests Boaz Yakin's Fresh in its programmatic subtraction of all popular culture from the lives of its child protagonists. (And, as with Fresh, GW was made by a white filmmaker who has been assumed to be black.) But, unlike Yakin, Green allows his performers remarkable space before the camera to simply be, whether surprisingly good or eloquently terrible" (J. Hoberman writing in the Voice upon the film's release in the fall of 2000).

§ Soon-to-be-forgotten things: "Passion," a short story by Alice Munro in the 22 March 2004 issue of the New Yorker, and Secret Window, another bad film I've watched out of devotion to Johnny Depp's career. I read the one and watched the other in a perfectly amiable and receptive state of mind, hoping for the best, but Munro's even competence was no more compelling than Secret Window's steadily-worsening stupidity and both, I suspect, will pass from memory with very little trace in the coming few days.

18 March — Thursday

§ David Thomson | "What Does a Snake Know, or Intend?" | Rev. of Where I Was From by Joan Didion | London Review of Books 26.6 | 18 March 2004 | 3-10

I find Thomson, the author of The Biographical Dictionary of Film, a less than scintillating prose stylist, but I kept at this long and somewhat haphazardly-structured overview of Didion's career in part because it's been so long since anyone I know or read has tried to make the case for her importance: "For forty years her attempt has been the most absorbing modern reading I know" (10). • On the new volume: the "wonder in Where I Was From is the way in which Eduene Jerrett Didion develops, piece by piece, as the the author's mother, yet as someone who, even at 90, remained inexplicable, or fictional—or as moving as she was because of things not settled or addressed. Here again, I think the characteristic obliqueness in Didion's work is a way of writing about people in fact and fiction as if they lived in the same remote or opaque place. 'Getting people'—or being mistaken about them—is one of the abiding perils in Didion's fearful view of the world. And surely she sees herself in a similar way as ungraspable, as close to breakdown as to lucidity" (6).

11 March — Thursday

§ Konvolut M | Screening notes for Jeanne Dielman, 23 Quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles and The Captive by Chantal Akerman | 11 March 2004 | link

"There are 24 years and many projects between these films. Still, after three straight nights of interminable static shots and intense formal rigor, [The Captive] felt more conventional than it probably is. I mean: There's plain old shot-reverse shot going on, p.o.v. shots, extra-diegetic music, the whole shebang. Compared to Dielman, this is Lawrence Kasdan."

10 March — Wednesday

§ George Steiner | "Zion's Shadows" | Rev. of Témoins du Futur by Pierre Bouretz | TLS 5265 | 27 February 2004 | 3-5

Steiner judges Bouretz's twelve-hundred page volume to belong to that rare genre of studies capable of "alter[ing] the intellectual landscape" (3): "More, perhaps, than any previous inquiry, Bouretz's investigation seeks out the fatal logic, the doomed appositeness of the flowering of Jewish genius—linguistic, philosophical, scholarly and literary—in the context of Imperial and Weimar Germany, a context which was to prove its annihilation" (3). • Steiner attempts, and more or less pulls off, highly-condensed profiles of the nine intellectuals treated in Bouretz's book: Hermann Cohen, Franz Rosenzweig, Martin Buber, Walter Benjamin, Gershom Scholem, Ernst Bloch, Han Jonas, Leo Strauss, and Emmanuel Levinas. • "What remains for Levinas is a kind of dynamic fundamentalism—a conviction that the only Messianic presence allowed to us is that of a just, compassionate life on earth. It is no accident that Levinas looks to Paul Celan's intimations of a God in need of man and of the equivalence between a poem and a handshake" (5).

9 March — Tuesday

§ Malcolm Gladwell | "The Terrazzo Jungle" | The New Yorker | 15 March 2004 | 120-27

Gladwell profiles the Viennese socialist who designed Southdale, a mall built just outside Minneapolis in the mid-1950s: "Fifty years ago, Victor Gruen designed a fully enclosed, introverted, multitiered, double-anchor-tenant shopping complex with a garden court under a skylight—and today virtually every regional shopping center in American is a fully enclosed, introverted, multitiered, double-anchor-tenant complex with a garden court under a skylight. Victor Gruen didn't design a building; he designed an archetype" (122). • Nice throwaway line: "shopping malls are, at bottom, delivery systems for lipstick" (12).

§ Kingdom Hospital | VHS tape of pilot episode broadcast by ABC on 3 March 2004 | 120min | link

I've not seen The Kingdom—Lars von Triers's "surreal soap" set in a Copenhagen hospital—but the Time Out capsule summary makes clear the extent to which this U.S. adaptation borrows central characters—a "universally loathed" consultant, a career patient (here played by Diane Ladd) "determined to exorcise from the building the unquiet spirit of a murdered girl," two basement dwelling "savants with Down's syndrome," etc.—while falling far short, in this first two hours at least, of meriting a description like the following: "Shot in breathless vérité-style, and marked by von Trier's customary jaundiced tone, it's a compulsive, bizarrely plausible witches' brew of interweaving storylines, conspiracy theories and paranoiac visions, held together by manic conviction right up to its Grand Guignol finale" (Wally Hammond, in Time Out Film Guide, 12th edition, 2004: 631).

8 March — Monday

§ Paul R. Krugman | "The Wars of the Texas Succession" | Rev. of American Dynasty by Kevin Phillips and The Price of Loyalty by Ron Suskind | New York Review of Books LI.3 | 26 February 2004 | 4-6 | link

Krugman dilates on John DiIulio's "Mayberry Machiavellis" remark with the help of two recent critical appraisals of the Bush clan's political conduct over the past several generations. • "Today there is, to an extent not seen since the 1920s, a substantial class of people wealthy enough to form their own dynasties. And in a variety of ways, from political contributions to more subtle shaping of culture, for example by promoting aristocratic values, this class has created an environment favorable for dynastic ambitions" (5). • "Bush's motivations are dynastic—to secure his family's rightful place. While he may have some policy biases—like that 'instinctive policy fealty' to the investment business—policy is basically there to serve the acquisition of power, and not the other way around" (6).

7 March — Sunday

§ Viktor Shklovsky | Third Factory | Introd. and trans. Richard Sheldon | Ann Arbor: Ardis, 1977 | Rpt. with afterword by Lyn Hejinian | Chicago: Dalkey Archive, 2003 | 106pp | $12.95

Martin Riker, a senior editor at Dalkey Archive currently residing in Denver, was kind enough to put the new edition of the book after which this website is named into my hands just minutes before my talk at the University of Denver on Friday. I read it, for perhaps the sixth time, in the air between Denver and Cincinnati on my return travels to Bangor. • "In brief, I see the matter in this way: change can and does take place in works of art for non-esthetic reasons—for example, when one language influences another, or when a new 'social demand' appears. Thus a new form appears in a work of art imperceptibly, without registering its presence esthetically; only afterward is that new form esthetically evaluated, at which time it loses its original meaning, its pre-esthetic significance" (58). • Read on-line excerpts from Third Factory in Context. • Read Martin Riker on Shklovsky's trilogy here.

2 March — Tuesday

§ Roger D. Hodge | "Weekly Review" | Harper's Magazine online | link

I've subbed up for the e-mail version of this feature after discovering it via a link on Reading and Writing. Makes a nice counterpoint to the Economist's summary of political and business news at the front of each print issue and the dull post-Raines Week in Review put out with the Sunday New York Times.

1 March — Monday

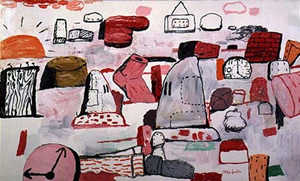

§ Raphael Rubinstein | "Philip Guston: Some Thoughts" | Art in America | March 2004 | 82-91, 141

"In 1977, [Guston] told an interviewer that when the 1960s 'came along' he was affected by 'the war, what was happening to America, the brutality of the world. What kind of man am I, sitting at home, reading magazines, going into a frustrated fury about everything—and then going into my studio to adjust a red to a blue" (91). • Rubinstein is careful, as always, to stress the poetic context for the painter's work: "It's no accident, I think, that Guston's writer-friends in the 1970s were nearly all poets in their 30s" (91). • Didn't know that Guston was the subject of a Life magazine feature story in 1946 ("several years before Pollock"). • Especially struck, among the reproduced images, by Couple in Bed (1977), which is at the Art Institute of Chicago. • Rubinstein concludes with a lengthy conceit involving Dylan and Guston simultaneously at work transforming their arts in Woodstock in 1967-1968: "like his guitar-playing neighbor, Guston had also retreated from the public stage (the New York art world) and the style that his fans had grown to expect from him (gestural abstraction)" (141). • Below, "Flatlands" (1970) posted on the Cioran63 site in August of 2003.

§ Lisa Duggan | "Holy Matrimony!" | The Nation | 15 March 2004 | 14-19 | link

"In a bid for equality, some gay groups are producing rhetoric that insults and marginalizes unmarried people, while promoting marriage in much the same terms as the welfare reformers use to stigmatize single-parent households, divorce and 'out of wedlock' births. If pursued in this way, the drive for gay-marriage equality can undermine rather than support the broader movement for social justice and democratic diversity" (18). • "Given the rising political stakes, and the narrow horizons of political possibility, it seems imperative now that progressives find ways to make room for a more integrated, broadly democratic marriage politics. To respond to widespread changes in household organization and incipient dissatisfaction with the marital status quo, progressives could begin to disentangle the religious, symbolic, kinship and economic functions of marriage, making a case for both civil equality and the separation of church and state. They could argue that civil marriage (perhaps renamed or reconfigured), like any other household status, should be open to all who are willing to make the trek to city hall, whether or not they also choose to seek a church's blessing. Beginning with the imperfect menu of household and partnership statuses now unevenly available from state to state, it might not be such an impossibly utopian leap to suggest that we should expand and democratize what we've already got, rather than contract our options" (18).

§ Andrew O'Hanagan | "Cartwheels over Broken Glass" | Rev. of Saint Morrissey by Mark Simpson and The Smiths: Songs that Saved Your Life by Simon Goddard | London Review of Books | 4 March 2004 | 19-21

O'Hanagan does a nice job with a delicate task: discussing two worshipful books about Morrissey without ridiculing the special form of transference that gave rise to them ("being a fan") or pandering overmuch to the manias and fantasias that sustain that transferential state. • "I was a Smiths fan," he confesses early on, "a position, I'd discover, only slightly less involving than being a Moonie, and the thing that made it so eminently sensible was that the person before us [i.e. Morrissey on stage] was a Smiths fan too — the ultimate fan — and his self-disgust and neuroses seemed to puncture the ethos of the 1980s rather nicely. The fans were outfanned by the object of their fanaticism: here was a pop phenomenon made up of pop phenomena — Morrissey's influences were the whole point of him, it seemed, and he understood hero-worship in such a manner as to make him a new sort of hero. He also knew how to hate Margaret Thatcher and the royal family, and he sent them up with an intoxicating vaudevillian glee" (19-20). • "The best thing about writing by fans is that it really matters to them: nobody wants to read a measured assessment of life on the road with the Rolling Stones. Fans must be capable of hating people who don't agree with them — they have to have the mentality of a teenager, in other words, as well as the acquisitive beakiness of the trains-spotter. But despite occasional enjoyment of one another's company, fans never really get on, and that's because it's in the fan's essential makeup to imagine that they are The Only One" (21). • While waiting for the on-line link to this article, due here on March 4th, check out Nicholas Spice's "I Must Be Mad," an energetically composed piece of witwork triggered by the recent re-translation of Freud's Wild Analysis which I somehow neglected to note here after admiring it in the 22 January issue of the LRB.

nb archive

June 1-15, 2003 • June 16-30, 2003